Duan Yongping gives a rare public interview more than 20 years after retirement: Buying stocks is buying companies, but less than 1% of people truly understand this statement.

Buying stocks is essentially buying into a company; the key lies in understanding its corporate culture and business model. Avoiding mistakes is more important than simply making the right decisions.

Original Source: Xueqiu

This is a rare public conversation with Duan Yongping, more than twenty years after his "retirement."

In the first episode of season three of the investment-focused professional program "Strategy," produced by Xueqiu, Xueqiu founder Fang Sanwen traveled across half the globe to meet face-to-face with this legendary investor in California, USA.

This hours-long conversation covered his life experiences, corporate culture, investment logic, and views on children's education—essentially a complete review of an investor's life.

In this interview, Duan Yongping mentioned “making mistakes” 10 times, “understanding” 12 times, and “very difficult” 29 times. Behind these words lies his consistent way of thinking: "Buying stocks is buying companies," but as he said in the interview, "Less than 1% of people truly understand this sentence."

The interview took place on October 16, 2025. The following is the full, unedited transcript.

Key Quotes

On Core Investment Philosophy

"Buying stocks is buying companies."

"Investing is simple, but not easy."

"You must look at the company, you must understand the business, and you must also understand future cash flows."

"Most companies are not easy to understand."

"Buffett's margin of safety does not mean cheapness; margin of safety refers to how well you understand the company."

"Cheap things can get even cheaper."

On Understanding and Not Understanding

"Understanding or not is actually a gray area."

"Not understanding does not mean not making money."

The saying "buying stocks is buying companies"—if 1% of people truly understand it, that's impressive, and actually achieving it is even harder."

On Rationality and Position Holding

"If you are dissatisfied, you should leave quickly; then it’s no longer in your hands. Otherwise, the logic doesn't hold."

"If I only had that much money, I might really have to sell."

"Staying rational is a very difficult thing."

"The probability of making mistakes is actually about the same for everyone; it's just that some people don't persist in their mistakes."

"(For me) after thirty years, the difference lies in making fewer of those mistakes."

On Looking at Companies

"Understanding business is very important; investing without understanding business is very difficult."

"I came from running a business, so understanding others' businesses is relatively easier, but I can't understand too many businesses either."

"I think I understand Apple, Tencent, and Moutai relatively well."

On Corporate Culture

A good culture mainly means that in the end, it will return to the right path, guided by a North Star, knowing what it should ultimately do. It's not just about business; discussing only business makes it easy to make mistakes.

"A company with a good culture doesn't mean it won't make mistakes, but that it can ultimately return to the right path."

On the Wisdom of "Not Doing"

"People care about what we've done, but a big reason we become who we are is because of the things we choose not to do."

01

Talking About Personal Experience

Fang Sanwen: This user asked a rather nonsensical question: How do you spend an ordinary day, for example, today?

Duan Yongping: Playing ball, exercising.

Fang Sanwen: Is it like this every day?

Duan Yongping: More or less, just playing on different courts.

Fang Sanwen: The only change is the location of the court and your playing partners?

Duan Yongping: Sometimes there are partners, sometimes not.

Fang Sanwen: A user named "Book Craftsman Old Zhang" wants to ask, what kind of environment did you grow up in as a child? Does that environment relate to your current personality or achievements?

Duan Yongping: I don't really know. I was born in Nanchang, and around age six, I went with my parents to Anfu County, Jiangxi. We moved five or six times in Anfu, always in rural areas, then moved back to Shigang near Nanchang. I did experience hardship; when we returned to Shigang, I started middle school, took the college entrance exam from there, and after graduating from university, was assigned to Beijing. After working for a few years, I did a graduate degree, then went to Guangdong, Foshan, Zhongshan, Dongguan, and finally came to live in California.

Fang Sanwen: I think maybe this user wants to ask in more detail—can you describe your family environment and what kind of education your parents gave you?

Duan Yongping: These things aren't that meaningful. How does it help him to know which river I caught fish in? It's hard to explain. I have an older brother and a younger sister; we all have different personalities. How much my parents helped, I really don't know.

But simply put, I think my parents were really good to us, not like many parents now who are very competitive and push their kids. My parents didn't really control me, didn't have many demands, so I felt pretty secure and could make my own decisions. I was used to making my own decisions from a young age, and I think that has a lot to do with my parents.

Fang Sanwen: You had plenty of freedom, and you think that's a good thing, right?

Duan Yongping: Yes, I think my parents had full trust in their children.

Fang Sanwen: Now that you're a parent, do you treat your children the same way?

Duan Yongping: Yes, I don't demand things from my kids that I can't do myself. If they want to play, I wanted to play at that age too. But I find that kids are pretty self-disciplined; they do their homework when they should, and so on. You have to tell them about boundaries—what they can't do. That's very important. It's not about lecturing them every day. I think giving kids a sense of security is very important; without it, it's hard to be rational.

Fang Sanwen: Set boundaries, give full trust?

Duan Yongping: Yes.

Fang Sanwen: During your childhood and teenage years, did you have any life goals?

Duan Yongping: I didn't have any goals. I've never been ambitious; I just see myself as an ordinary person, and it's enough to live a good life.

Fang Sanwen: So you could say your goal was just to live well?

Duan Yongping: I didn't even think that much. I never thought I had to achieve something or accomplish something. I just do what I like and feel happy.

Fang Sanwen: During your childhood or teenage years, did anyone ever describe you as different from others?

Duan Yongping: I remember in middle school, a teacher said, "Duan Yongping, you can't just play and not study like the others." I don't know why the teacher said that—maybe because I was a good student, and I was. When I took the college entrance exam, I crammed and got in. Most people in my era couldn't get into college, so maybe the teacher was right, and I didn't let him down—I got into college.

Fang Sanwen: He probably thought you were at least stronger than others in terms of learning ability, so he had certain expectations for you?

Duan Yongping: It was a strange thing. He was an English teacher, and my English was terrible. Why he thought I was a good learner, I have no idea. I only learned English in college, not in middle school. But that English teacher said I was different from other kids. When someone says you're different, you really remember it.

Fang Sanwen: But at least it was motivating for you.

Duan Yongping: I just remember it. I didn't think it was a big deal. If you hadn't mentioned it, I would have forgotten; now that you mention it, I remember.

Fang Sanwen: You majored in engineering as an undergraduate, then did a graduate degree, which I guess was in business. Did your interests change during this process?

Duan Yongping: Actually, no. First, I want to stress that I didn't study business; I studied econometrics, which is economics. I think it's also engineering—it's a very logical discipline. After college, I was assigned to Beijing Electron Tube Factory, helped in the personnel department for over half a year, then went to the education center and taught adult math for over two years. Then I found it boring, had a chance to take the graduate exam, got into Renmin University, and wanted a change. I wasn't that interested in my engineering major. People are always exploring, trying to find what they like. Renmin University helped me.

Fang Sanwen: Do you think what you learned in college had a big impact on your later life?

Duan Yongping: I think the main thing in college is learning how to learn, building confidence that you can learn things you don't know. That way, you're less afraid of the future. Otherwise, you'll be scared of everything. I've seen many people who can't even type on a smartphone. I find that strange. I couldn't type before, but I learned quickly and developed a habit of learning. Graduate school was like switching to a new field, gaining new knowledge, and a slightly different perspective. But the main thing was getting out of my original environment. We were poor students back then, couldn't even afford to travel. I went to school, got a new job, and learned a lot along the way, though it was tough.

Fang Sanwen: So the specific knowledge you learned wasn't that important?

Duan Yongping: Method and attitude matter. The confidence that you can learn things is very important. When you encounter something you don't know, you think about learning it, not being afraid. Many people are afraid. I tried to teach my mom to use an iPad 20 years ago, and now at 100, she definitely won't learn. Even when she was in her 70s or 80s, she refused to learn, thinking she couldn't. But it's actually very simple and has nothing to do with age.

Fang Sanwen: After graduate school, you went south to Guangdong. How did you make that decision?

Duan Yongping: I could have stayed in Beijing; two organizations wanted to hire me. Then a Guangdong company was recruiting in Zhongguancun, so I went, but it wasn't ideal, so I switched to Zhongshan.

Fang Sanwen: So going south to Guangdong was, in a way, you embracing the market?

Duan Yongping: No, we actually had no other options, so we tried it. I was young, so trying was good. I have a habit: if something doesn't suit me, I leave quickly. Beijing wasn't right for me, so I left. I didn't know what Guangdong would be like, but staying somewhere I didn't want to be was unreasonable, so I left. I even considered Hainan, but after learning about it, decided Guangdong was better.

So I think if your decisions are based on the long term—what you want your future to be—the probability of making mistakes is lower. Many people asked, "If you go to Guangdong, what about retirement?" I said, "At my age, why think about retirement? I need to go out and see the world." Maybe I was lucky and chose the right path. Actually, many decisions were because I felt uncomfortable in the environment and had to leave. Even after arriving in Guangdong, I left my first job after three months. I think I chose the right path but entered the wrong door, so I left. Then I went to Zhongshan, started Subor, and did very well, but due to the system, I felt it wasn't right and left again.

Fang Sanwen: Can you talk about what was wrong with the system specifically?

Duan Yongping: At first, we were told we'd have shares. The boss first said 30/70, then 20/80, then 10/90. I recruited people and made promises, but couldn't fulfill them because with 10/90, eventually there'd be nothing. By 1994 or 1995, I knew it wouldn't work and decided to quit.

Fang Sanwen: So quitting involved two things: you wanted equity incentives, and you wanted a good contractual relationship?

Duan Yongping: It wasn't about equity incentives, because there were at first. Without a contract, you're not trustworthy. If you break your word once or twice, will there be a third time? It's like scratching a bottle cap—if you see "Sorry" after one character, you stop. When I saw that, I knew I couldn't stay. I left Subor 30 years ago and then went to Dongguan to start BBK.

Fang Sanwen: When you started BBK, did you clearly solve the problems you encountered at Subor?

Duan Yongping: The problem at Subor wasn't the lack of a shareholding system, but not fulfilling promises. We never had that problem from the start. We were always what we said we were, and everyone worked well together. What we said was what we did, so everyone felt secure and trusted each other. I think the original boss regrets it now.

Fang Sanwen: Looking back, was it possible to achieve an ideal governance structure under Subor's system?

Duan Yongping: I don't know how to answer that. In fact, no. I don't know what would be ideal, because it wasn't my problem—it was someone else's. I didn't leave because of money, but because of trust. I was already earning well and financially free. The profit sharing was there, but I didn't know what would happen in the future. Whether they could establish a shareholding system or make you feel secure in the mechanism—I don't know. Some companies treat dividends as a favor, but that's not right. Dividends are what shareholders deserve; bonuses are what employees deserve. When we give bonuses, some say "thank you, boss," but that's not appropriate—it's contractual, so you don't need to thank me. People say thanks out of habit, but it's not necessary.

Fang Sanwen: When you started BBK, did you consciously create the corporate culture you liked?

Duan Yongping: Corporate culture is closely related to the founder. You find people who agree with you and your culture. Our corporate culture is simply that everyone agrees with it, so they stay; those who don't agree are gradually eliminated. It's not like I wrote a corporate culture document from the start and made everyone follow it. Our culture evolved over time, including our "not-to-do list," which was added item by item, often learned through painful lessons. Since I stopped being CEO over 20 years ago, the company has become much stronger. Back then, we were a small company, but still impressive—even Subor was impressive.

Fang Sanwen: Can you briefly summarize the corporate culture that has formed over the years?

Duan Yongping: We always talk about integrity, honesty, and user orientation. Our values are very straightforward. Our vision is "healthier and longer-lasting"—we don't do things that are unhealthy or unsustainable. It's all about a normal mindset.

Fang Sanwen: A user said you thought of the "integrity culture" in your third year of college. Is that true?

Duan Yongping: In my third year, I accidentally read a quote from Drucker: "Do the right things and do things right." It had a big impact on me. It brings out the right and wrong in things. If you spend five seconds thinking about whether something is right, you'll save yourself a lot of trouble in life. In our company, when we discuss whether a business is profitable, we ask, "Is this the right thing to do?" If it feels wrong, we stop easily. If you only consider profit, things get complicated, and you often don't know in advance. But for some wrong things, you can tell early. Of course, sometimes you only realize after the fact, and that's okay—just don't do it again.

I can give you a simple example: we don't do OEM. It's not a principle—OEM can make money, but we're not good at it. Once, Terry Gou asked me about this, and I said we have a not-to-do list. He asked for an example, and I said we don't do OEM. He asked, "What do you mean?" I said, "If I do OEM, I can't beat you, right?" He agreed. But we're good at branding, and our company isn't smaller than theirs. It's not that OEM is bad, it's just not suitable for us, so we simply don't do it. Anyone who comes to us for OEM business, we just say no.

Fang Sanwen: So you have a value system about right and wrong first, and then a methodology for how to do things?

Duan Yongping: Yes. Learning has a cost and a curve, and you might make mistakes. If you're doing the right thing and make mistakes in the process, that's acceptable. But if you do the wrong thing and suffer the consequences, that's not okay—because you knew it was wrong. Of course, if you didn't know beforehand, just don't do it next time. Over decades, this means making fewer mistakes and not going in circles.

Fang Sanwen: A user called "Learning Machine" asked whether people with shared values are mainly cultivated or selected?

Duan Yongping: Selected.

Fang Sanwen: Are the outstanding talents at BBK not necessarily recognized at the start, but cultivated over time working with you?

Duan Yongping: Most people are like me—ordinary. We share values, have a college education, and learn as we go. But value alignment is very important. If values don't align, things can't work. If everyone has their own agenda, there will be problems. At our 30th anniversary, many old colleagues were still there, some even after retirement, some still working.

Fang Sanwen: So, according to you, doing the right thing and finding the right people—selection is more important?

Duan Yongping: Finding the right people takes time. There are two types: those who aren't right and are gradually eliminated, and those who have both good and bad sides but, after agreeing with your culture, follow you. We always say we have two types of people: like-minded people and fellow travelers. If they agree with you, even if they're confused, they'll do as you say. Sometimes they make mistakes, but they can come back. People who stay a long time have this opportunity. Our agents over the years have also been great, with strong cultural alignment.

02

Talking About Business Operations

Recommended Reading:

CZ mass unfollowing: Is the absurd "attention business" completely over?

Rewriting the 2018 script: Will the end of the US government shutdown = a bitcoin price surge?

1.1 billions USD stablecoins evaporate: What's the truth behind the DeFi domino explosion?

MMT short squeeze review: A carefully designed money-grabbing game

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

The US SEC and CFTC may accelerate the development of crypto regulations and products.

The Most Understandable Fusaka Guide on the Internet: A Comprehensive Analysis of Ethereum Upgrade Implementation and Its Impact on the Ecosystem

The upcoming Fusaka upgrade on December 3 will have a broader scope and deeper impact.

Established projects defy the market trend with an average monthly increase of 62%—what are the emerging narratives behind this "new growth"?

Although these projects are still generally down about 90% from their historical peaks, their recent surge has been driven by multiple factors.

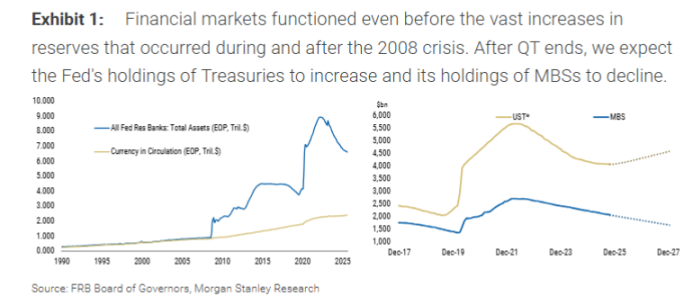

Morgan Stanley: Fed Ending QT ≠ Restarting QE, Treasury's Debt Issuance Strategy Is the Key

Morgan Stanley believes that the Federal Reserve ending quantitative tightening does not mean a restart of quantitative easing.